Help is Not on the Way (at least not immediately)

As draft day approaches, a fog of excitement and apprehension swirls around the top international talents. Most international players, even the projected top-of-the-first-rounders, have had limited exposure in the U.S. market and are untested against the domestic college pool. By necessity, this leads to a certain level of extrapolation. Comments like If this guy was playing major college basketball, hed be a better prospect than Al Horford abound every year. For players projected to go later in the draft, there is an additional enticement: a team may draft an international player and keep him playing overseas for a couple of years and thus off the teams books as they dance around the luxury tax threshold. This time of year, every team is searching for that player that will ferment, refine, and spring forth as the next Manu Ginobili.

But Fran Vazquez, selected 11th by Orlando in 2005, reminded all NBA GMs that there is an additional element of risk with the international player: that he may never come at all, never even attempt to play. While this is a rarity for first round picks, fans constantly hear that their teams second round pick could really be a solid contributor someday. But will tomorrow ever come? And if it does, will it look like Manu?

Definition of the International Player

The term International Player has been used differently by a number of writers. Some have included players such as Tim Duncan (Virgin Islands) or Steve Nash (Canada) as international players because their birthplace was not the United States. However, for the purposes of assessing talent in the draft, we feel that the most common usage would cast anyone who went to college in the US as a domestic player, whatever country is printed on his birth certificate, and even if he came to college directly from his country of origin. For the present analysis, we therefore define international players to be those who on draft day have not played high school or college basketball in the US. Were talking about Ben Pepper, Yi Jianlian, Pau Gasol, and Arvydas Sabonis, not Patrick Ewing or Dikembe Mutombo.

The Presence of the International Player in the NBA Draft

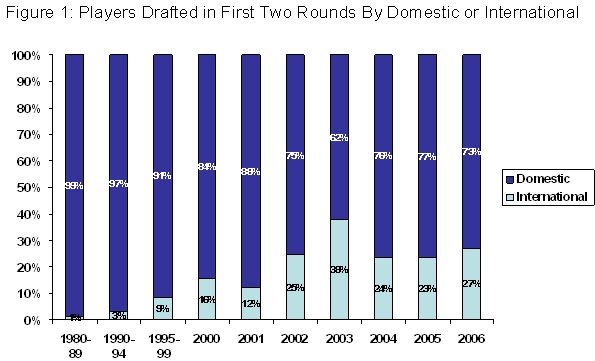

Prior to 1995, international players in the NBA draft were a rarity (Figure 1). In the late 90s, the number of international players drafted slowly grew. Then in the past five years, the market for international players really exploded, with a remarkable peak in 2003 when more than 1 out of every 3 players drafted was an international talent. Just two years prior the number had been only 1 in 8. Over the last three drafts about a quarter of the players selected have been international prospects. Given the historical paucity of international talent, this article will generally examine only players drafted since 1995.

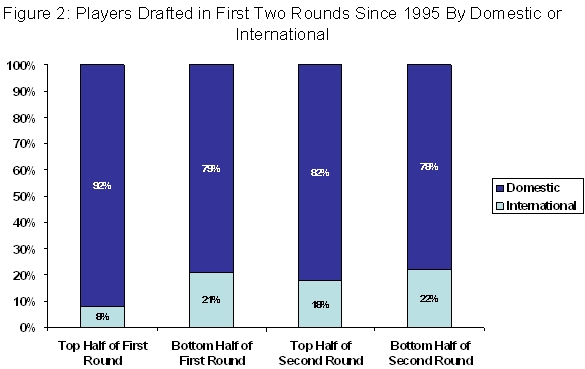

In recent years, international players have been chosen throughout the draft, but are more likely to go in the second round. In the top half of the first round (largely lottery picks) international players are rarely selected (Fig. 2). In the twelve drafts from 1995 to 2006 only eight international players were selected in the top ten: Yao Ming (1), Andrea Bargnani (1), Darko Milicic (2), Pau Gasol (3), Nikoloz Tskitishvili (5), Nene Hilario (7), Dirk Nowitzki (9), and Saer Sene (10). However, once you get past the top half of the first round, the density of international players settles into approximately 1 in every 5 players. Again, as Figure 1 showed, these rates are higher in more recent drafts.

Appearance in the NBA

International players, once drafted, are less likely to play in the NBA than are their domestic counterparts. There have been 121 international players drafted in the twelve years since 1995. Forty-five of those players (37%) are still on layaway for NBA teams. Taking three years as a reasonable waiting period for eventual player appearance (i.e, considering the drafts only from 1995 to 2004), lowers the figure slightly to 31% (28 of 91). Essentially all first round draft picks (domestic or international) see time in at least one NBA game. The only exception in the 10 drafts from 1995-2004 was the legendary Knick selection Frederic Weis (the 15th pick in the 1999 draft). Of course, as mentioned earlier, Vazquez may soon join this inauspicious short list.

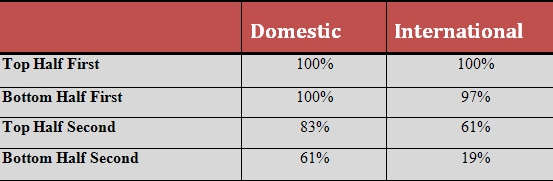

The second round is where the roulette wheel really starts spinning (Table 1). In the years from 1995-2004, 172 of the 241 domestic players drafted in the second round (71%) played some time in the NBA. However, for international players that percentage is cut in half: of the 50 second round international draft picks, only 19 (38%) have ever played in the NBA. Of those 31 players who have never played, 28 are still listed on RealGM as the property of some NBA team, indicating that they have never attempted to play in the NBA. Perhaps some NBA teams are just fine with this arrangement; given the low likelihood of NBA success for second round picks (see our previous article) teams may take a flier on these lesser-known players hoping to hit the jackpot someday. If they dont ultimately pan out, at least the team has not sacrificed much.

[c]Table 1: Percent Drafted Players from 1995-2004 Who Ever Play in the NBA[/c]

[c]Table 1: Percent Drafted Players from 1995-2004 Who Ever Play in the NBA[/c] With the increased drafting of international players in recent years, one wonders whether the likelihood of NBA matriculation is increasing. While it is probably too early to make a final determination, the initial answer is: no. Among second round international draft picks: from 1995 to 1999 only 23% (3 of 13) matriculated within 2 years; in 2000/2001 this number jumped to 50% with a smaller sample size (4 of 8); in 2002/2003 it receded to 15% (3 of 20); and finally for the 2004 and 2005 drafts the number matriculating returned to 21% (4 of 19). For the most part, the waiting game for international second round picks continues.

Delayed Appearances

For a variety of reasons, teams wait longer for international players than for their domestic counterparts. Ninety-one percent of domestic players who will ever play in the NBA are on a team the year that they are drafted. Meanwhile, only 67% of international draftees who ultimately play in the US will play here the year that they are drafted. By the year following the draft, essentially all of the domestic players who will ever play in the NBA have appeared, while close to a quarter (22%) of the international players have yet to arrive.

The grandfather of all potential international saviors was Arvydas Sabonis, described before knee injuries abridged his mobility as a Russian Bill Walton. The NBA waited a decade for Sabonis after he was initially drafted in the fourth round in 1985 by the Atlanta Hawks and again in the first round in 1986 by the Portland Trailblazers (in that era if a team did not sign a player before the next draft, they ceded his rights and he became draftable again). However, there are other Internationals who made the NBA wait several years as well, with Efthimios Rentzias leading the non-Sabonis contingent, suiting up for his first game seven years after being drafted in 1996. Dino Radja and Peja Drobnjak also made their teams wait; both played their first NBA game in their fifth season of eligibility after being drafted. Most international players who end up coming to the NBA, however, are seen within three years of being drafted.

If you ever utilize the Real GM TradeChecker (TM) you will notice some players shaded in grey at the bottom of team rosters with no salary attached to their name. These are players who have been drafted by NBA teams, but have never played in the NBA. Their rights are still held by either the team that drafted them or a team that has obtained their rights via trade. These players have never attempted to make an NBA roster, as if they had and were cut the NBA team would no longer hold their rights. Fifty-seven players are thus listed on RealGM, and 47 of those meet our definition of international (82%). Marcelo Nicola, drafted in 1993 by the Houston Rockets and now owned by the Portland Trailblazers wins the prize as the player drafted the longest ago who is still owned by an NBA team. San Antonio, the gold standard of the league in many ways including the drafting of foreign players, currently owns the rights of 5 international players, and is tied with Portland for the most of any NBA team.

Success in the NBA

International players, once they arrive, have clearly made their mark on the NBA in some very high profile ways. This season provides an excellent example with an international MVP, three international players in the primary rotation of the NBA champions, and about half of the rotation of the NBAs most pleasant surprise (led by the Coach of the Year winner): the Toronto Raptors. But how widespread is this success? How likely is it that your teams international pick (if and when he arrives) will develop into the next Manu?

To allow a window for fair evaluation, we will again consider the 1995 through 2004 drafts (although the jury may still be out on players like Darko Milicic, even at this range). First: how often do teams hit a home run with their international selections? Nine of the 91 (9.8%) international players drafted in these 10 years have gone to at least one All Star game: Yao Ming, Pau Gasol, Dirk Nowitzki, Peja Stojakovic, Zydrunas Ilgauskas, Andrei Kirilenko, Tony Parker, Mehmet Okur, and our eponymous Manu Ginobili. This number, while respectable, is only slightly higher than the domestic player rate over the same time period (7.8%). Among those who have ever played in an NBA game, the gap widens a little, as 13.8% of drafted internationals have made an All Star team compared with 9.1% of domestic players. Note that for the 50 international second rounders drafted, only 2 (4%), guess who (Manu) and Okur, have ever made an All-Star team; however only 4 of 241 (1.7%) domestic second round draft picks in those 10 years can claim the same accomplishment (Gilbert Arenas, Michael Redd, Rashard Lewis, and Carlos Boozer).

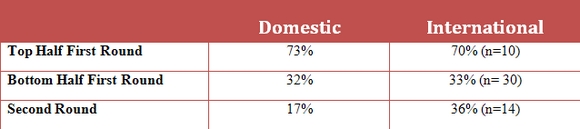

Beyond the star level, international players who spend time in the NBA tend to play similar minutes to those domestic players drafted in the same range of the draft. For example, by their second year in the league, about 73% of domestic players drafted in the top half of the first round are regular rotation players (playing at least 20+ minutes per game) with the international rate nearly the same (70%, although based on only 10 players). The rates are nearly identical in the second half of the first round as well. In the second round, once international players matriculate (among those who do matriculate), they seem more likely to be rotational players than do their domestic counterparts (although this is based on only 14 players). This makes sense, as foreign players wait longer to matriculate, and are thus more mature than domestic players by their second NBA season. Also, those international players who do matriculate are likely doing so because they have a sense (or overt promise) that they will actually get playing time, otherwise they would opt to stay with their current foreign team.

[c]Table 2: Percentage of Drafted Players 1995-2005 Who Played in at Least One NBA Game Who Average 20+ Minutes per Game in their Second Season[/c]

[c]Table 2: Percentage of Drafted Players 1995-2005 Who Played in at Least One NBA Game Who Average 20+ Minutes per Game in their Second Season[/c]Conclusion

First round international players drafted over the past decade have followed a similar pattern of NBA involvement and success as their domestic counterparts. They appear to pose no greater risk than domestic players, and offer similar rewards. Second round draft picks, on the other hand, have largely been enigmas, names on rosters that become punch lines on team blogs (on CelticsBlog, the use of Ben Pepper has taken on a universal meaning of its own). Few of these players ever set foot into an NBA training camp. Among those who do, there have been a handful of contributors and a couple of stars. However, the supreme success of the 57th pick in the 1999 draft has yet to be replicated.

The landscape is certainly changing. The sheer volume of international players drafted over the past five years reflects a seismic shift in the culture of the NBA. There have clearly been attempts to seek out international players and incorporate them more widely into the league. Thus far, the results of attempting to lure these second round prospects to the NBA have been mixed. The NBA must compete with foreign club and national teams for a players rights and there are sizable buyouts for some players that make accepting a restricted NBA salary financially impossible for them. Some top international players can command salaries outside the NBA that would be significantly higher than what they could garner as a role player here. However, it is clear that many NBA teams would love to have a consistent third or fourth scoring option, which seems to be an increasingly rare commodity, and the international pool appears to be a valuable resource for such players. Expansion has more broadly distributed the domestic talent pool in the NBA, and a potential solution seems to lie beyond our borders. Bridging need and solution would seem a priority for NBA franchises.

Other Gearan and Allen Columns can be found here

Note: Data for this article was compiled from NBA.com, Basketball-Reference.com, NBADraft.net, DatabaseBasketball(2.0), DraftExpress, and TheDraftReview.com. The authors would like to thank all those involved with developing and maintaining those resources and making them available for public use.

Comments